Decoding the Mysteries of Medically Unexplained Neurologic Diseases

Using advanced research techniques, Rutgers Health–led scientists have shed light on how chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia are related, paving the way to even bigger breakthroughs.

New research may create some respite for sufferers of two medically unexplained fatigue-inducing conditions: myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and fibromyalgia (FM).

The conclusion, and the methods used to reach it, could inform how these and other conditions – such as multiple sclerosis, long COVID, Alzheimer’s and post-treatment Lyme disease – are diagnosed and treated.

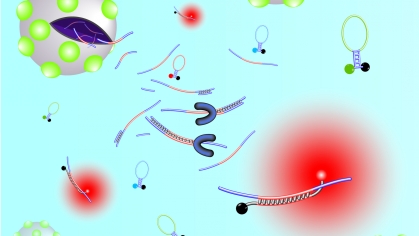

“Using mass spectrometry to analyze spinal fluid, the liquid that bathes the brain, we found that these two illnesses may fall along a common disease spectrum,” said Steven Schutzer, a professor of medicine at the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School and lead author of the study published in the Annals of Medicine.

“The results have implications for how the conditions can be investigated, while the technique may help advance treatment approaches with these diseases, and many others,” Schutzer said.

Based on older data, specialists have long debated whether ME/CFS and fibromyalgia, which share overlapping neurologic symptoms, are distinct or related central nervous system conditions.

Schutzer and co-researchers, including Benjamin Natelson, director of the Pain and Fatigue Study Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, believe they have opened the door to solving one piece of the ME/CFS-fibromyalgia puzzle.

To determine whether ME/CFS and fibromyalgia are distinct or related, researchers used mass spectrometry to examine proteins in spinal fluid in 30 patients. Half of the patients had confirmed cases of ME/CFS and fibromyalgia, and the other half had only ME/CFS.

By using advanced mass spectrometry to test the spinal fluid, researchers were able to conduct an unbiased assessment of samples’ proteins. This enabled the team to identify and quantify proteins that may be of diagnostic and therapeutic importance, a technique that is applicable to the study of other diseases.

Their analysis yielded convincing evidence of a relationship, Schutzer said. Of the 2,083 proteins quantified, 1,789 proteins were present in both samples.

“There do not appear to be discrete [cerebrospinal fluid] proteins for ME/CFS, which allow that group of patients to be clearly differentiated from those for ME/CFS + FM,” the researchers wrote. “Thus, this proteomic study did not support the hypothesis that ME/CFS has an entirely different underlying pathophysiology from CFS + FM in the [central nervous system]."

Additional research is warranted to validate the findings, and a particular focus should be put on studying proteins in patients presenting with only fibromyalgia, the researchers noted. But Schutzer said he is hopeful the new method used, combined with more data, will help in the search for effective therapies for a host of neurologic conditions.

Millions of patients stand to benefit. A 2015 report by the National Academy of Sciences found that as many as 2.5 million Americans suffer from ME/CFS, which causes extreme fatigue lasting months to years. Similarly, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates 4 million people – 2 percent of the U.S. adult population – live with fibromyalgia, a chronic disorder that causes pain, tenderness and fatigue.

Advances in mass spectrometry analysis facilitated the research, said Schutzer. Previously, researchers needed large volumes of spinal fluid to run individual tests, but improved methods have made it easier to generate data with smaller samples.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Other authors included Tao Liu, Chia-Feng Tsai, Vladislav A. Petyuk, Athena A. Schepmoes, Yi-Ting Wang, Karl K. Weitz and Richard D. Smith from Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, and Jonas Bergquist, from Uppsala University, Sweden.