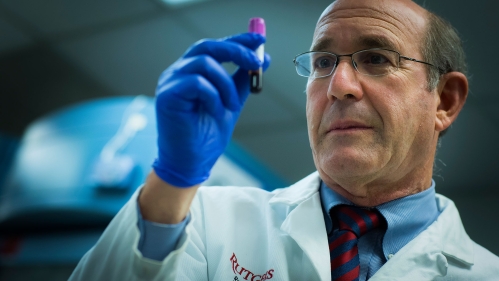

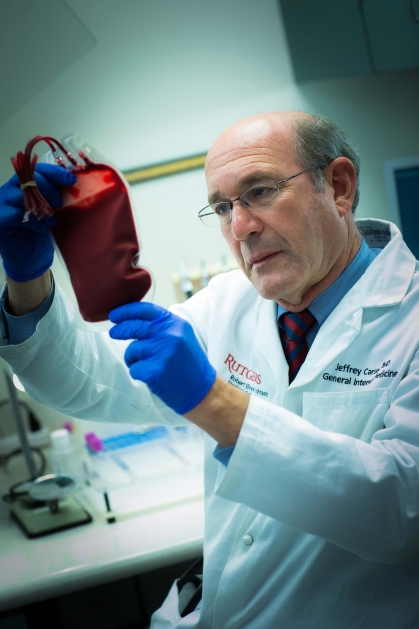

How a Doctor’s Blood Transfusion Research Is Changing Standards and Saving Lives

Jeffrey Carson spent more than a decade persuading hospitals that fewer, resource-saving blood transfusions work just as well as more frequent transfusions for most patients. More recently, the Rutgers internist finished a massive study that indicates a major exception to the rule: anemic heart attack patients.

That work, published in late 2023 in the New England Journal of Medicine and reinforced by a combined analysis of patients from several studies this past winter, underpins a just-published recommendation from the Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies (AABB) to give more-frequent transfusions to patients suffering myocardial infarction.

The AABB joins the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association in making this update. Their acute-coronary-syndrome guidelines now state clinicians should consider giving enough transfusions to keep blood hemoglobin, which brings oxygen to cells, near 10 grams per deciliter in anemic patients who have suffered heart attacks – significantly more than the current standard of 7-8 grams per deciliter

“I'm very proud of this trial,” said Carson, a Distinguished Professor of Medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and provost at Rutgers Health. “To have results that actually will change practice and that are in guidelines in such a short period of time after trial publication (1.5 years) is very rewarding.”

Each year, about 200,000 Americans who suffer heart attacks also have anemia (low levels of hemoglobin). Adopting a liberal strategy (giving more blood to maintain a higher hemoglobin level) could prevent 4,800 recurrent attacks or deaths and 3,200 deaths annually, Carson’s study found. All this would require an extra 366,000 pints of blood, slightly more than 3% of the 10 million transfused nationwide each year.

The two new guideline papers are the first to break from more restrictive transfusion recommendations urging fewer transfusions that keep hemoglobin at 7-8 grams per deciliter for all anemic patients. Ironically, these recommendations were largely the result of Carson’s earlier transfusion studies.

“Yes, there’s some irony in spending decades demonstrating that liberal transfusions are unnecessary, though certainly not harmful, and then turning around and finding a major exception where liberal transfusions are justified,” said Carson. “But you go where the evidence leads and embrace the practices that will save lives.”

Carson’s fascination with blood transfusions began in the early 1990s, when he was caring for Jehovah’s Witness patients who refused blood on religious grounds.

This work created a natural experiment on the value of using transfusions to maintain normal levels of blood hemoglobin, which delivers oxygen to all the cells in the body. Each patient who declined transfusion faced surgery and its aftermath with whatever hemoglobin their bodies naturally had, so they gave Carson his first evidence of two facts he would spend the next several decades establishing more rigorously:

- Most patients fared just as well with hemoglobin levels of 7-8 grams per deciliter, so guidelines calling for enough extra blood to keep it at 10 are likely wasting a lot of blood

- People with serious heart problems fared better with higher hemoglobin levels, so giving more transfusions might help their care.

“Jeff has now changed clinical medicine twice in the past 25 years. He has had more influence on the way we transfuse these days than anyone else,” said Aaron Tobian, professor of pathology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and director of the Transfusion Medicine Division at Johns Hopkins Hospital. “He has been the most curious, inquisitive and persistent person in this field of research, trying to figure out what is best for patient care.”

Carson’s first grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded a 1996 Lancet study of more than 2,000 Jehovah's Witness surgical patients. It revealed that as hemoglobin dropped, mortality rose more sharply in those with cardiovascular disease than in healthier individuals.

This led to observational studies and systematic reviews of all research that synthesized transfusion trials. His 2011 FOCUS trial of more than 2,000 frail hip-fracture patients showed restrictive and liberal strategies produced identical survival and mobility, cementing the notion that “less is more” for most surgery and intensive-care cases. The study became the backbone of successive guidelines that urged clinicians to wait until hemoglobin dipped to about 7-8 grams per deciliter before ordering red cells.

Overall, across thousands of patients, restrictive strategies reduced blood use by about 40% without increasing morbidity or mortality.

“Using more blood did not improve outcome, but it also did not harm patients,” Carson said.

Yet the same early data that set Carson on his minimalist path also hinted that ischemic hearts, which are suffering from insufficient blood supply, might be different.

“If the engine is starved for oxygen, taking away more fuel never sounded smart,” he said.

For a small, 2013 trial, Carson enrolled 110 patients and reported seven deaths in the restrictive (lower) group versus one in the liberal (higher)-transfusion group. Those results were far from definitive, but they were enough for Carson and colleagues to secure $17 million from the NIH for a major study.

Carson and University of Pittsburgh statistician Maria Brooks co-led the Myocardial Ischemia and Transfusion trial. Between 2017 and 2023, 144 hospitals on five continents randomized 3,504 heart-attack patients whose hemoglobin had fallen below 10 grams per deciliter. The restrictive group received transfusions only if the level fell under 8 grams per deciliter. The liberal group was topped up immediately and received an average of 2.5 units of blood versus 0.7 in the restrictive arm. Thirty days later, 14.5% of liberal-strategy patients had died or suffered another heart attack compared with 16.9% in the restrictive group.

The trend fell just shy of statistical significance but raised eyebrows across the cardiology community. Although there was a small chance the improved outcomes from the more generous transfusion strategy were a statistical anomaly, there was a much larger chance that more blood worked better. Crucially, there was no sign of harm from the extra blood.

Because the clinical signal was persuasive but not definitive, Carson’s team pooled individual patient data from the Myocardial Ischemia and Transfusion trial and three earlier trials, totaling 4,311 volunteers. Restrictive care was linked to a 47% higher risk of cardiac death at 30 days and a modest but significant rise in six-month all-cause mortality. Those numbers landed on the desks of guideline writers just as they were closing drafts. Carson recused himself from the vote, but several committee members said the data spoke for themselves.

“We finally have data strong enough to act on,” said New York University’s Sunil Rao, who chaired the writing group.

“For most patients, we proved you can safely use less,” Carson said. “For heart attack patients, we now have to use more transfusions.”