Rutgers Health at 10: Interprofessional Education for Better Health Outcomes

University bolsters collaborative capacity of health professions students to improve health care quality and communication as well as the patient experience

Maybe it was a misplaced decimal point on a patient’s medication dose. Perhaps it was vague instructions given quickly during a shift change. Or was it a surgeon’s domineering style of working that discouraged the other members of the health care team from speaking up?

It’s estimated that every year as many as 98,000 Americans die because of medical errors that occur in hospitals. Many of these deaths – more than those from breast cancer, AIDS or motor vehicle crashes – can be traced to poor teamwork, inadequate or non-compliance with safety procedures, and far too often, poor communication.

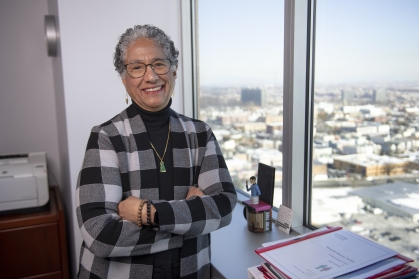

“Anytime someone dies from an error in a hospital there are lots of after-action reports to shed light on what happened,” said Denise Rodgers, vice chancellor for interprofessional programs at Rutgers Health. “One of the things that we’ve learned as a profession is that more often than not, poor communication played a role.”

To strengthen the collaborative capacity of Rutgers’ health professions students – many of whom will be New Jersey’s future health care professionals – Rutgers Health has doubled down on efforts to improve the way its graduates work with colleagues across disciplines.

Training is focused on two key philosophies: interprofessional education (IPE) and interprofessional collaborative practice.

Interprofessional education is designed to help students from two or more health-related professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration. At Rutgers, students across many disciplines – from nursing to dentistry, from medicine to social work – partner in practical exercises to solve problems and improve the patient experience.

A set of interprofessional core competencies guide the development of interprofessional education activities at Rutgers and throughout the country. An additional component of IPE is the inclusion of teachings about TeamSTEPPS, a patient safety program developed by the Department of Defense and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Students also learn by doing. For instance, students from 11 schools and programs, including nursing, medicine, public health, pharmacy and laboratory science, partner in an annual stroke case-based exercise to plan a patient’s care over the course of several weeks – from their presentation in the emergency department to rehabilitation at home. The training is meant to facilitate the knowledge of roles and responsibilities of all members of the patient care team as well as help students learn about the importance of shared decision-making.

“When someone has a stroke, it’s doctors and nurses who save their life, but it’s everyone else who gives them their life back,” Rodgers said. “It’s the occupational therapist who teaches them how to eat again and physical therapists teach them to walk again. It’s the psychologist who helps them deal with their new reality, especially if they are grappling with depression. It’s the social worker who addresses practical issues like whether their house needs wheelchair access. Social workers can also help to address mental health issues. Everyone who plays a role in that stroke patient’s life is part of their health care team. We teach Rutgers’ students what that means and how it should work in practice.”

Health care educators have understood the value of interprofessional education and teamwork since the 1970s. But it wasn’t until 1999, when the independent, non-government U.S. Institute of Medicine released a series of reports focused on overhauling health care in America, that cross-disciplinary learning became a priority for the nation’s health professions schools.

In 2013, when the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ) merged with Rutgers, strengthening collaboration across schools, units and departments, Rodgers, then president of UMDNJ, was appointed head of the RBHS Office of Interprofessional Programs. Before taking the helm, Rodgers took a six-month sabbatical, traveling the U.S. to study best practices of other interprofessional programs.

Today, Rutgers Health is a leader in the collaborative medical education field, offering dozens of undergraduate, graduate, master’s and dual-degree programs and partnering with other Big 10 schools to share methods and ideate on things like facilitator training. Rodgers leads a team of health care professionals dedicated to facilitating the development, implementation and evaluation of interprofessional education and research within and between schools, clinical units and institutes.

Although required for accreditation, interprofessional education is much more than a box-ticking exercise. The outcome – interprofessional collaborative practice – has been linked to improved patient health and fewer medical mistakes.

A 2023 literature review, co-authored by researchers at Rutgers’ health sciences libraries, found that several health metrics – including medical errors, patient satisfaction and length of hospital stay – are positively impacted when medical professionals have been properly trained to work collectively.

“To improve the quality of patient care, health care professionals must not only work together as a team, but learn together as a team,” the authors concluded.

There also is evidence that members of high functioning teams have greater job satisfaction, Rodgers said.

As with many aspects of health care, COVID-19 complicated the interprofessional picture. As burnout pushed nurses to retire or quit, hospitals were forced to look for nurses from other regions simply to cover shifts.

“What this meant is that somebody from North Dakota might be working one week, and then somebody would fly in from Florida to work the following week. How can we even think about creating coherent health care teams when people don’t know their colleagues?” Rodgers said. “What we are attempting to do at Rutgers Health is to say, ‘Let’s give learners basic skills in teamwork and collaboration, so that they have the ability to work with anyone at any time, from anywhere.’”

Rutgers’ medical centers, clinics and affiliated hospitals have plenty of room for improvement, Rodgers said. No organization is perfect. But at Rutgers Health, students have an opportunity to learn with other students representing more than a dozen different disciplines – and that’s a unique strength here.

“As we seek to train a new generation of health care professionals in team-based care we remain ever mindful of the challenges we face as we strive to reduce and eventually eliminate disparities in health outcomes by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status,” Rodgers said.

RBHS 10th Anniversary

In 10 years, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences (RBHS) has seen transformational achievements that have catalyzed us, changed Rutgers, and benefitted New Jersey and our valued partners and communities.