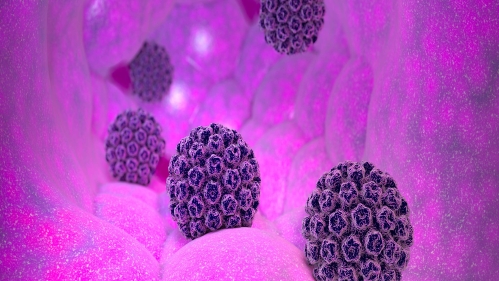

Previous sexually transmitted infections and more sexual partners predict new human papillomavirus (HPV) infections in men who have sex with men, other cisgender sexual minority men and transgender women, according to a Rutgers study.

“Neither of those findings is unexpected, but they’re both important,” said Caleb LoSchiavo, lead author of the study published in the American Journal of Men’s Health and a doctoral research assistant at the Rutgers Center for Health, Identity, Behavior and Prevention Studies (CHIBPS). “Anal HPV infections cause about 90 percent of all anal cancers, and high infection levels among these groups lead to elevated cancer rates. We are just now doing the work to analyze what’s actually happening so we can design effective intervention strategies.”

Previous studies have noted high rates of HPV infection among sexual minority men and transgender women, but the new study followed 137 of them – all young residents of New York City – for up to five years to see which factors predicted new infections with those strains of HPV that create a high risk of anal cancer (hrHPV).

All patients underwent testing on three occasions: when they entered the study, roughly two years later and about two years after the first follow-up visit.

At the initial visit, 31.6 percent of patients tested positive for an anal hrHPV infection. The two subsequent visits found new hrHPV infections in 27 percent and 29.9 percent of patients. Over the course of the study, 57.7 percent of participants tested positive for at least one strain of hrHPV at one or more study visits, while 42.3 percent never tested positive.

“This study illustrates the urgent need for more intervention,” LoSchiavo said. “HPV vaccination could prevent these infections, but vaccination is rare in this population because it was originally approved exclusively for young women and is still associated by patients and medical providers alike as a way to prevent cervical cancer in women. That has to change.”

Vaccination can’t treat existing HPV cases, and no other treatments exist, but screening is still important, LoSchiavo said.

“People need to know if they have high-risk HPV so they can opt-in for extra cancer screening,” LoSchiavo said. “Extra screening catches problems early, allows doctors to remove growths before they become cancerous, and saves lives.”